| At the start of this year, Steven Paynter had a problem: his niche was no longer so niche.

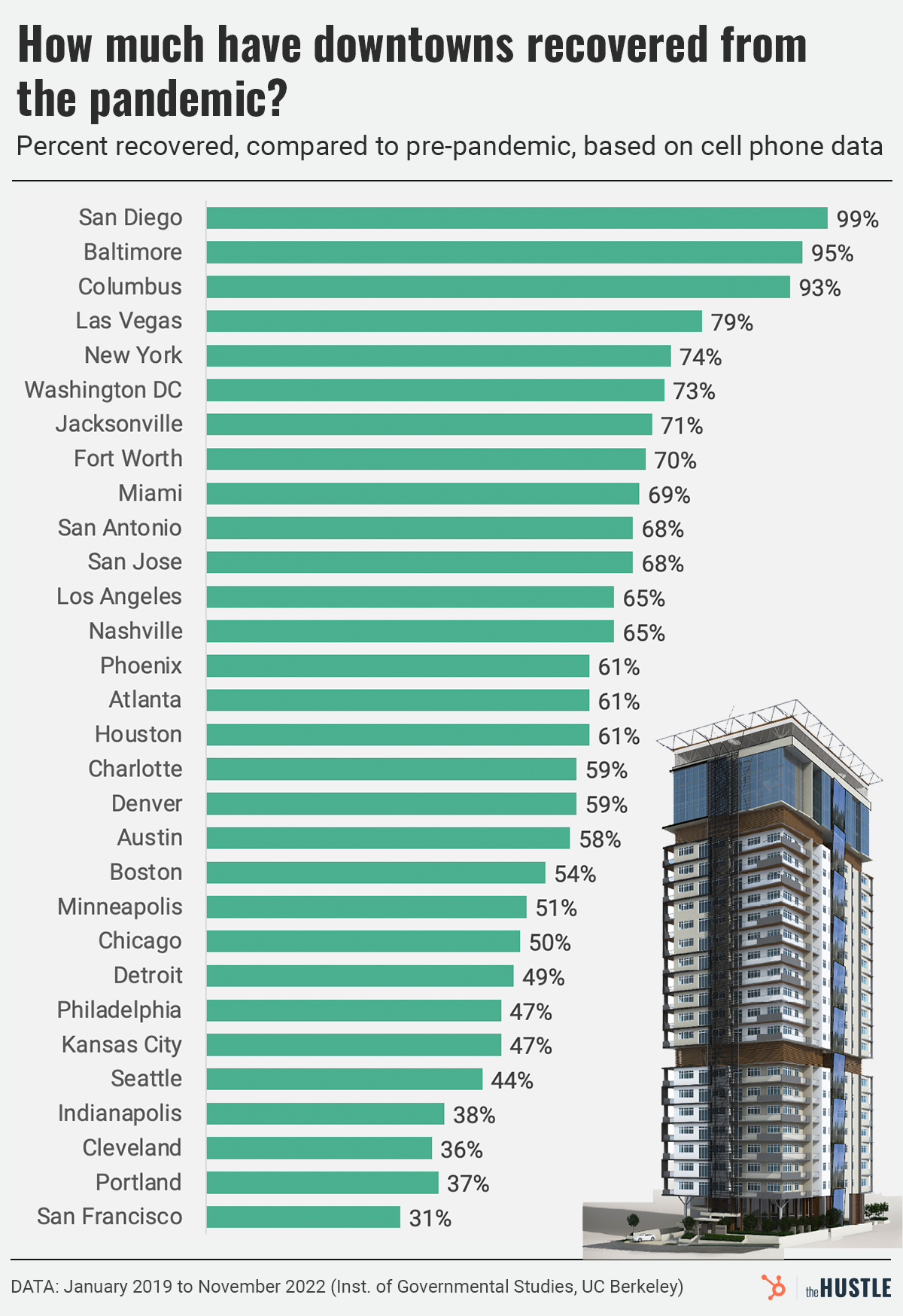

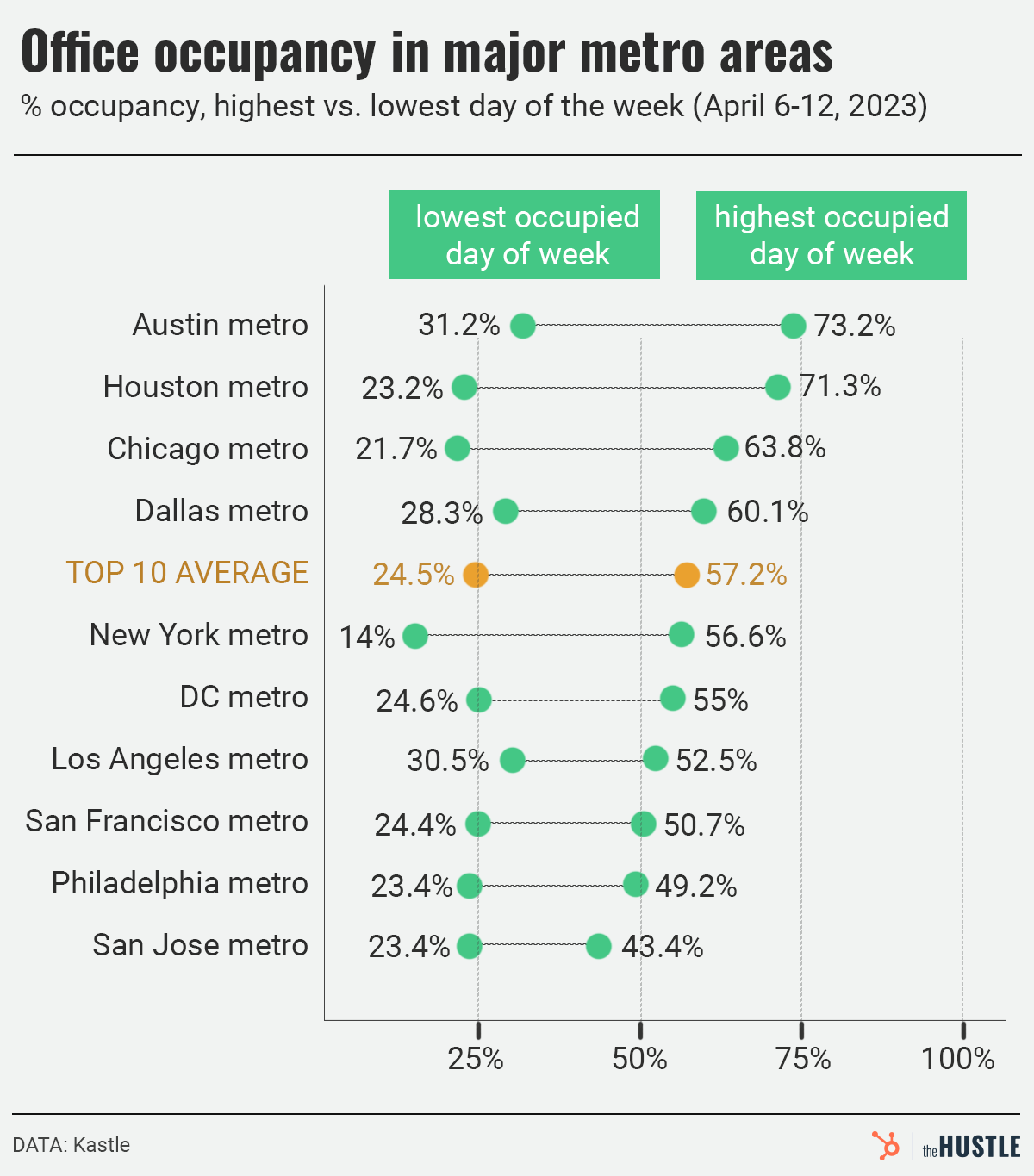

Paynter leads a studio of 40+ architects at Gensler, one of the world’s largest design and architecture firms. Just before the pandemic, he’d developed a new, bespoke offering: transforming sad, old office buildings into nice, new apartments and condos. Then the pandemic shut down offices, and droves of workers never returned. In downtowns across America — in cities such as New York, Houston, and San Francisco — office buildings are still 40%-60% vacant. Local politicians see a crisis to be solved: Unless they are transformed — a daunting, difficult prospect — downtowns could become ghost towns. But for some developers, the problem is an opportunity to shop for discount real estate in the center of North America’s most expensive cities. Recently, a client asked Paynter to look at 12m square feet of mostly vacant office buildings in downtown Calgary, wondering if they could be turned into happy homes for urbanite Canadians. “It’s been crazy,” says Paynter. “It’s a huge number of projects and a huge amount of work.” A long time coming?Work has long defined the geographic center of American society. “Over the last hundred years, we designed the world around the office,” says Dror Poleg, an economic historian and author of Rethinking Real Estate and After Office (forthcoming). “It determined the center of our cities, the length of our commutes, and other business activity that was influenced by the rhythms of the office.” “And I think that in 50 or 100 years, we will look back at this moment as the clear point when that paradigm broke.” For the past two years, the demise of downtown office districts has been headline news. “San Francisco’s downtown as we know it is not coming back,” Mayor London Breed said in February. |

|

But America’s downtowns were not thriving pre-covid. As Poleg and Paynter point out, the pandemic and remote work accelerated corporations’ already-in-progress retreat from downtown — a trend driven by two chief factors:

Still, cities and landlords were not planning for the scale and pace of change that the pandemic brought. “As recently as a year and a half ago, when I would try to write something in The New York Times about converting offices into housing, they’d respond, ‘Dude, don’t be so crazy,’” says Poleg. “It’s not, ‘Okay, we were going there anyway, and [the pandemic] just accelerated everything by two years or five or ten.’ There is a dramatic break here.” This is not just a problem for landlords. With fewer office workers, the restaurants and cafes that cater to them are struggling: A recent JPMorgan Chase analysis found that cities such as Chicago, Miami, and San Francisco had up to 6.5% fewer retail establishments than they did pre-pandemic, and the closures are concentrated downtown. (Many suburbs, in contrast, have seen growth.) And these losses could lead to a potential doom loop:

|

|

But in cities like Boston and San Francisco, where land is scarce and zoning laws and residents have opposed the construction of new high-rises, the crisis also looks like a once-in-a-generation opportunity.

Finding a golden ticketFor years, companies in New York coveted the offices in the 22-story high-rise at 25 Water St. The owner, JPMorgan, was the anchor tenant, and the luckiest employees in the building — located between Wall Street and Battery Park — had views of the waterfront or NYC’s skyline. But when JPMorgan put the building up for sale recently, Brian Steinwurtzel only saw apartments — not offices. “We immediately began exploring whether we could convert it,” says Steinwurtzel, co-CEO of the venerable NYC real estate firm GFP which leases office space across the tri-state area. One reason was the building’s facade — it not only needed work, but its narrow windows were better-suited to archers defending a castle than letting loads of light into a sun-drenched office. If they had to invest in windows anyway, it was easy to imagine installing apartment windows. Steinwurtzel also gently describes office buildings as, “you know, a very difficult sector in real estate these days.” |

A rendering of what 25 Water St. will look like after conversion and construction work (courtesy of CetraRuddy) |

Most importantly, Steinwurtzel says, 25 Water St. had three key ingredients needed to successfully buy an office building and convert it into residences:

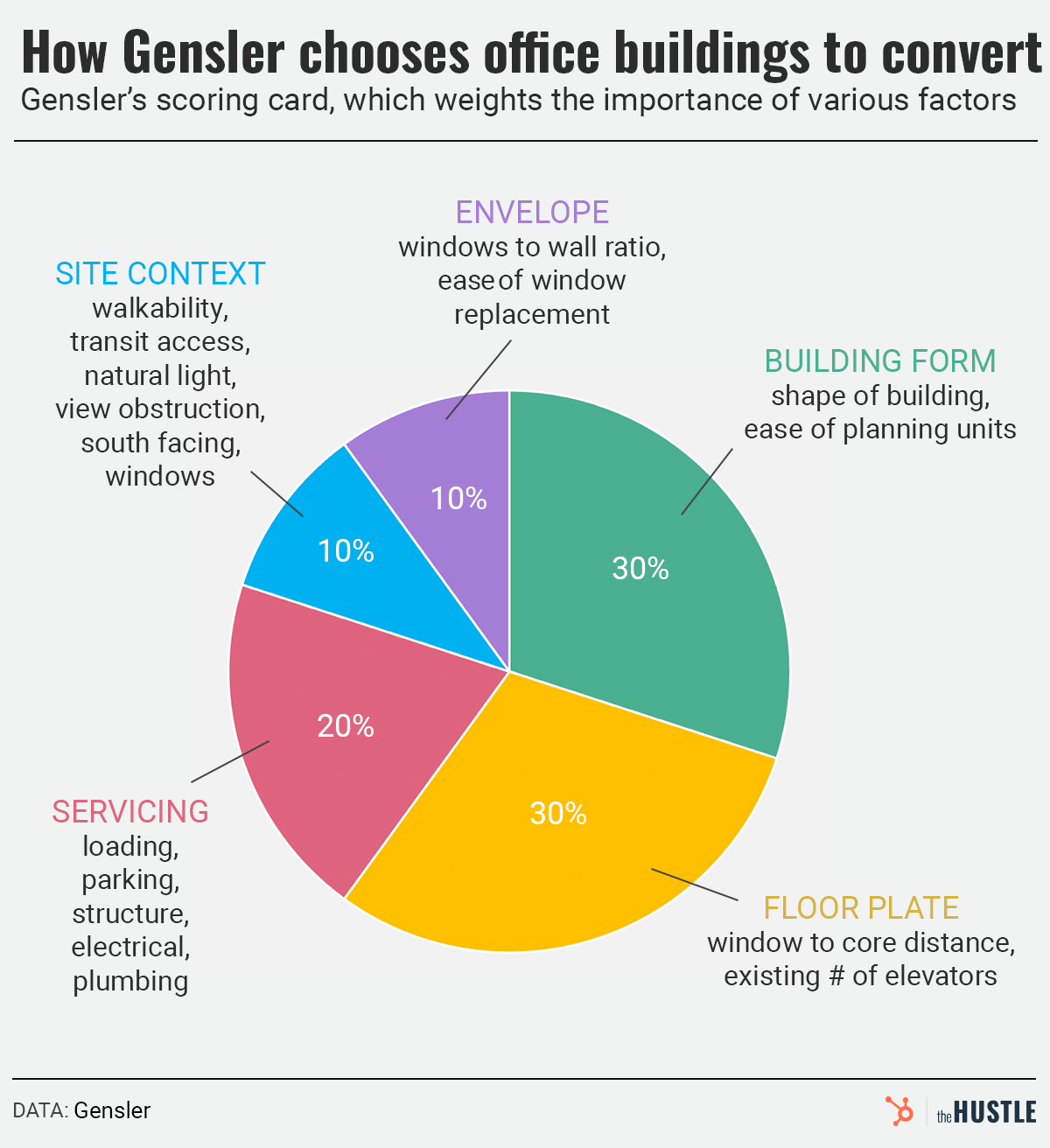

Steinwurtzel’s list of ingredients focuses on business factors. But even under these circumstances, not every office building can transform into residences without breaking the bank. Some buildings’ physical layout will never translate to cozy condos and agreeable apartments. That’s why the score card Paynter and his team ultimately developed at Gensler — to keep up with the demand for evaluating offices’ potential for residential transformation — focuses on architectural features such as:

|

The Hustle |

| Gensler’s algorithm scores office buildings from 0 to 100; any that score above 80 are good candidates for conversions.

Or, as Paynter put it during our conversation, finding an office that scores above 80 is “like a golden ticket — if you can find those, you can do great.” Why housing?Apartments and condos are not the only possible use for underutilized office buildings. They have been converted into hotels and science labs and various industrial buildings. But despite all the challenges of turning dreary, beige offices into attractive apartments, Paynter says, those other uses tend to be rare and challenging. In fact, housing is the most obvious way to adapt underperforming offices. That’s because…

Demographic data supports the belief that people want to be downtown. Since 2021, the population of big cities ranging from Miami to NYC has nearly rebounded from the early-pandemic exodus, with Manhattan in particular seeing population growth in 2022. Many analysts doubt they will fully recover. But Poleg believes the pandemic and WFH will lead many big cities to get even bigger, and to thrive — perhaps like never before — if they can meet the moment. |

Commercial developers debate how work-from-home trends will affect the future of America’s downtowns (Image: Pixabay) |

| Poleg compares cities in the WFH era to music in the streaming era: Although YouTube and Spotify made it easier than ever for us to find and listen to niche bands, streaming increased the dominance of superstars like Beyonce and Taylor Swift.

That’s because it’s easier than ever to listen to Taylor Swift and because, when facing limitless options, most listeners choose the easiest, most obvious option. (Another comparison: It’s easier than ever for tourists to learn about charming Italian cities and villages. But they still overwhelmingly visit Venice and Cinque Terre.) Similarly, an increasing number of remote workers can choose to live anywhere, or anywhere within certain time zones. But most urbanites will choose the Taylor Swifts of city experiences: central neighborhoods in New York, London, and Singapore where they can walk to busy bars and find food that is trending on TikTok. Being the default-choice city, though, takes as much work as dominating the charts, which means city policy is essential to ensuring that turning offices into apartments is profitable and productive. SimCity modeAt Gensler, Paynter often hears from landlords who are interested in converting their office buildings or developers interested in buying and converting a building. He also hears from mayors and city planners. The client that wanted to evaluate 12m square feet of Calgary’s downtown? That was Calgary Economic Development, a nonprofit affiliated with the city government. Paynter has also worked with San Francisco, Portland, cities across Canada, and others he can’t disclose. |

Downtown San Francisco is among the nation’s hardest-hit areas (City of San Francisco) |

| He’s presented, too, to Mayor Eric Adams of New York City, which recently released an “adaptive reuse” study that’s already led to legislative and policy changes to boost the number of office-to-residential conversions.

NYC’s study describes conversion as “a niche pathway for office building owners,” and Steinwurtzel cautions that conversions are “one of the riskiest things a developer can do — there are so many unknowns behind every wall, floor, and ceiling.” These difficulties are why mayors and city planners believe developers alone can’t solve their downtown problem, and why many are pursuing changes to zoning requirements and offering incentives — not only to stimulate the transformation of office buildings, but to ensure these conversions include affordable housing and solve lingering urban issues. Consider a recent NYC planning report focused on “[reimagining] New York’s commercial districts as vibrant 24/7 destinations.” The report suggests:

Across America, it’s initiatives like these that will determine which cities and downtowns attract residents and workers with their Taylor Swift-esque quality of life — and whether an increasing number of office conversions are profitable and transformative. Even Paynter, who believes the industry is underestimating how many offices are good candidates for conversions, doesn’t call office conversions “golden tickets” because they’re like winning the lottery. It’s because he believes that, amid a set of unviable options, they are a hidden opportunity. |